Some months ago, I was asked to participate in an event honoring one of Arkansas’s true pioneers of higher education, Professor Joseph Carter Corbin, the founder of Pine Bluff’s Branch Normal College, later renamed Agricultural, Mechanical & Normal College (AM&N) and known today as the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff. The event, a celebration of Corbin’s life and work, would take place on September 27, designated as “Joseph Corbin Day.”

The invitation was extended by Dr. Gladys Turner Finney, a retired social worker and academician, proud graduate of AM&N and author of a biography of Professor Corbin, published by Butler Center Books in 2017. During my time here I have corresponded with Dr. Finney, as she has gifted her research files and other materials bearing on African American life and education in Arkansas to the ASA. I accepted, not knowing exactly what could bring to the event; I enjoyed her very readable Corbin biography, did a little reading on my own and waited for further instructions.

A couple of weeks before the event, I received the draft of the program; I was scheduled to present between remarks by two powerful, dynamic speakers: Dr. Charles Robinson, historian and Chancellor of the University of Arkansas-Fayetteville, and Ms. Ashley Crockett, broadcaster and journalist. My assignment was to talk—briefly!—about “Professor Corbin’s contributions to education in Arkansas.”

To prepare, I revisited Dr. Finney’s book and looked for collateral sources, hoping to find something new to add to Corbin’s story. My first script attempt ran to somewhere north of 6,000 words; subsequent revisions whittled this down to under 1500 words or so, but the big problem remained: I, the invited outsider, would be talking in front of people who must know far more about Corbin than I ever would; what could I bring to this story? What could I contribute?

On the day, what I brought was something I realized I shared with Corbin: an outsider’s perspective. Neither of us was an Arkansas native; we both arrived here in, roughly, our “young middle age.” And neither one of us ended up doing, I think it is safe to say, what we expected to do when we arrived here. With this as a mental starting point, I somehow made it through my notes, editing on the fly and occasionally verbally “tripping over my shoelaces.” What follows is what I meant to say, or tried to say, while doing my at-lectern revision.

***

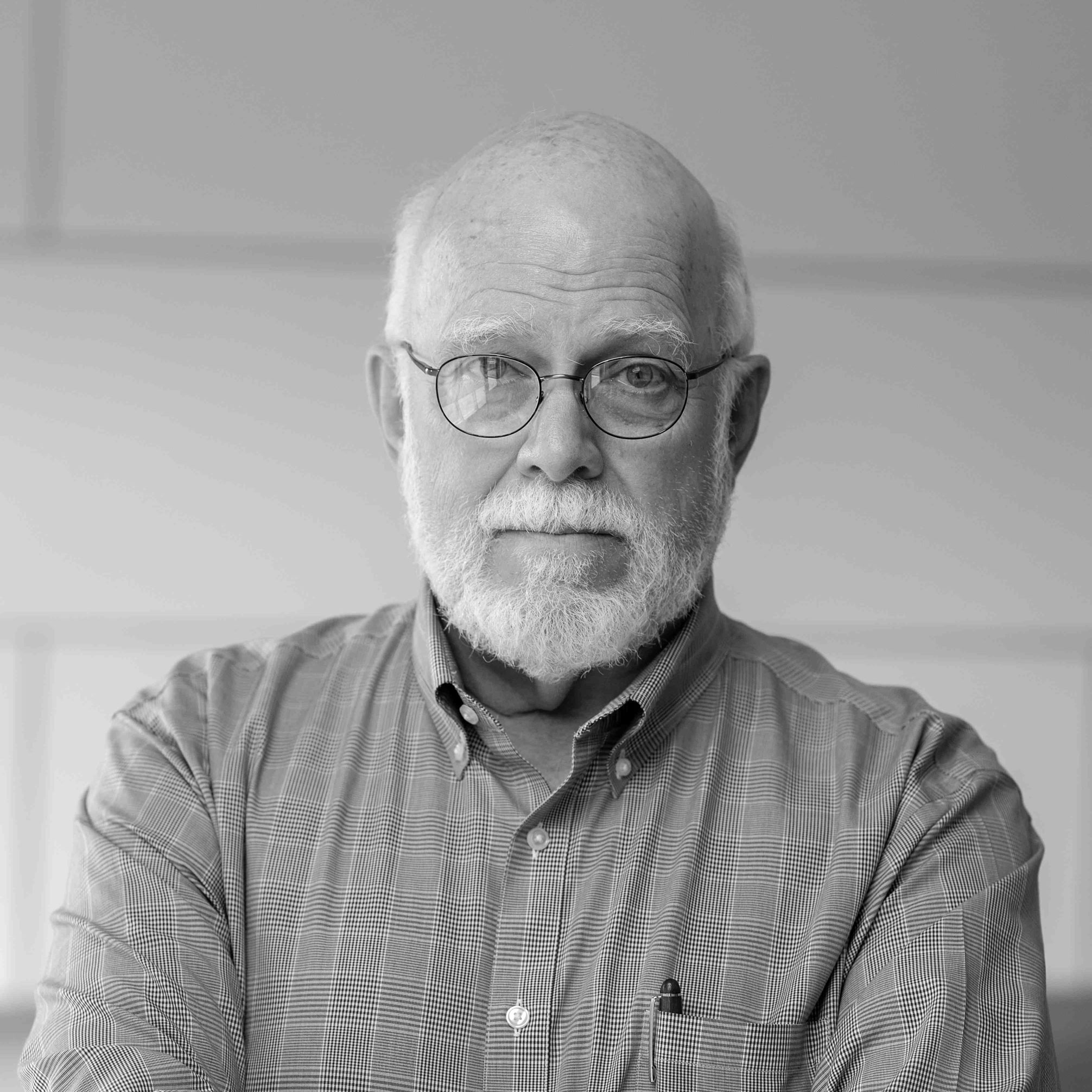

Portrait of Joseph Carter Corbin, superintendent of public instruction from 1873-1874. (Arkansas State Archives)

Professor Joseph Carter Corbin was a remarkable man, a remarkable educator, one who saw the future as it might be, should be, and worked to make it happen by working in education.

What did he contribute to education in this state?

First, he brought a broad, generous liberal arts education. He was the son of formerly enslaved parents, born and raised in Ohio. In 1850, he enrolled at Ohio University in Athens—a public university. He was not the school’s first African American student, but the third…and the second to graduate, with his B.A in 1853, M.A. in 1856.

The person who earned those degrees came out of the Ohio University a broadly-educated well-rounded individual: on the “menu” for Ohio undergraduates at that time was instruction —with the expectation of acquiring proficiency—in Latin, Greek, the New Testament (read in Greek), geography, logic, arithmetic, geometry and algebra, “natural philosophy”—the physical and biological sciences, to thee or to me—and “the general principles” of history, the English language, the law, grammar and rhetoric, criticism, surveying and even navigation! This curriculum should make it clear: the “liberal arts” imparted to Joseph Corbin were not simply training for an occupation, but education for one’s whole life.

Corbin also brought engagement: working with the Underground Railroad in the 1850s, working as a teacher in Kentucky, then as a bank clerk in Cincinnati. While in Cincinnati during the years of the Civil War, he was active in a literary society, helping found a weekly newspaper for African Americans in the Midwest—On its front page the paper, The Colored Citizen, proclaimed, paraphrasing Roman playwright Terence, “Nothing that Concerns Mankind is Foreign To Me.” I think that, maybe, Corbin’s classical roots were showing.

He demonstrated engagement, too, in things that mixed education and…politics. while in Cincinnati, Corbin was a member of the local Colored School Board; he served a term on the board in the mid-1860s and again in 1870-71.

Service on a school board may not sound exceptional or even worth mentioning but consider the times. Beginning about 1850, the city of Cincinnati, following Ohio law, set aside the taxes on African American-owned properties for what were styled the “Colored Public Schools.” Black adult males elected the school board, the only election in which they could vote. By the mid-1850s the Colored Public Schools of Cincinnati controlled the education of African American students in east and west-side “Common Schools”; within a few years, the system included the John I. Gaines High School and a “Normal School”—that is, a modest seminary for teacher training. It was this system in which Corbin ventured to take a role in governance.

The board was small, and I would guess that there was no room on it for individuals who simply wanted a title to add to their resume. Instead, the board was divided into committees, with board members each serving on three or four. The Cincinnati Colored School Board Annual Report for 1864-1865 reveals that Corbin served on four committees: Textbooks (that is, effectively the curriculum); Printing (responsible for forms and papers, as well as issuing the annual reports which were almost certainly required by law); Salaries; and Fuel (coal and wood to heat the schools and, probably, dealing with the other practicalities of maintaining the buildings). Corbin would seek and win a second term, for the 1870-1871 school year, navigating in twin currents of education and politics that would carry him south by southwest in 1871…to Arkansas.

Corbin left Ohio for Arkansas in 1871. What called him here? Dr. Finney admits that what drew Corbin to Arkansas is not fully known, but I suspect that his willingness to be engaged and active, coupled with good prospects of advancement and, possibly, political connections, all played a part in his move. In Arkansas at that time, the Republican Party was dominant, thanks in part to the disenfranchisement of many former Confederates. The party embodied a fusion of interests: former Unionist native Arkansas whites, Unionists from outside the state, drawn here by a combination of economic opportunities and desire to reform the state from its old, bad habits; and freedmen, the formerly enslaved, accorded political rights, if not social equality, by the “Reconstruction Constitution of 1868." Corbin’s political connections in Ohio would almost certainly have been with the Republican party—the party of Lincoln, the party identified with emancipation—and those likely political connections seem to have served him well. He arrived in Little Rock in 1871 and quickly demonstrated something else he would bring to education in Arkansas: flexibility. He went to work as a reporter for The Daily Republican, that party’s Little Rock organ, and as assistant Postmaster in Little Rock. He was “a coming man”, certainly one of the best-educated men in the state of any race. I suspect that he made connections, made friends, impressed party leaders as a generally and genuinely capable individual—and in 1872, was elected the state’s Superintendent of Public Instruction on the Republican ticket, taking office in January 1873.

Soon into his tenure, Corbin was approached by two white teachers -- M.W. Martin of Pine Bluff and Alida Clark of Helena--about the idea of a normal school, to train black teachers for Arkansas. At the end of the war there had been only five such in the state, and the Reconstructionist state government was committed to providing education to African Americans.

Library at the Arkansas Agriculture, Mechanical and Normal College, Pine Bluff, Jefferson County (Photo: Arkansas State Archives)

Corbin, I conclude, “worked” his connections, calling into being a committee of three notables—two state Supreme Court justices and one state senator, John Middleton Clayton, brother of former Governor, U.S. Senator and Republican party chieftain Powell Clayton--to come up with a plan and a way to make this happen.

What emerged from this committee’s work was the Act of April 25, 1873, which established the Branch Normal College, a subsidiary of the Arkansas Industrial University (Today’s University of Arkansas -Fayetteville) to be located somewhere southeast of Pulaski County and appropriated 25,000 dollars in order to get it started by the fall of 1873.

But… things did not quite work out that way. The Republican Party’s internal dissent, which led to the “war” of 1874, the constitutional convention of that summer, the ousting of most Republican officeholders and the effective end of Reconstruction in Arkansas led to Corbin losing his office; In the fall of 1874, Corbin headed north into Missouri to teach, and there he might have stayed, his Arkansas interlude at an end, except that he was called back to Arkansas by Democratic governor Augustus Garland in the late summer of 1875. Corbin was offered a job, to establish the normal school at Pine Bluff.

Corbin brought his educational accomplishments, his talent for engagement, and his flexibility—after all, he was a staunch Republican, dealing with a former Confederate leader and one of the smartest, most capable lawyers ever to emerge in this state--to the job. And in return, the job brought him something just as important: a mission.

On August 18 1875, Corbin was commissioned to establish and run the normal school, at the princely salary of $1,000 per year. He was the principal and, until 1883, the sole regular faculty member, working for the first few years in rented space, teaching a first class of seven students. Over the next decade, he grew enrollment, while broadening the mission from simple teacher training to more general education—and the school grew. Branch Normal’s enrollment grew from seven students in 1875 to 241 by 1894. A two-story brick building with classrooms and an assembly hall and a women’s dormitory were built. An industrial department was established with courses in sewing, typing, and printing—these vocational courses were added between 1880 and 1900. Corbin himself wrote articles on mathematics and constructed mathematical puzzles. While at Branch Normal, he conducted teacher training institutes in Arkansas and the Permanent Indian Territory (Oklahoma), believing that such courses inspired teachers to improve…in effect, performing missionary work for the profession of teaching.

While accomplishing these things, Corbin evidenced one other, crucial “contribution” to Arkansas education: persistence. Informed by that sense of mission, he was a fighter for the school: In 1891, after the Arkansas Legislature adopted provisions of the federal Second Morrill Act of 1890, providing support for land-grant colleges, Corbin sought to have its measures implemented, in particular the expectation that if a state maintained separate white and black land grant colleges, funds should be "equitably divided," although equity was left for states to define. Perhaps predictably, many states opted to divert most Morrill Act funding to their whites-only institutions, leaving schools serving African Americans with scant funds on which to survive, let along thrive. Arkansas was—and long remained-- one such.

Dormitory at the Arkansas Agriculture, Mechanical and Normal College, Pine Bluff, Jefferson County (Photo: Arkansas State Archives)

But at the time, Corbin met with some success. The Arkansas Assembly allocated $5,000 to create new programs in agriculture and “mechanical arts” at Branch Normal, and hired William S. Harris, a white employee of the Fayetteville University of Arkansas campus, to run the new programs. Corbin was not entirely happy with this outcome: he felt that agriculture did not offer his students many opportunities for upward mobility but these courses were the price of Morrill Act funds: his heart was in the liberal arts but he was a practical man, persistent and intent on making the college persist as well.

He was even less happy in 1893, when the Democratic legislature tried to get him fired because of “poor performance”; this year was also the last one in which an African American held a seat in the State House until the 1970s. The attempt failed, but the Legislature forced the University’s Board of Trustees (remember that Branch Normal was still essentially a dependent of the University of Arkansas) to promote Harris to Superintendent and Treasurer of Branch Normal, effectively undercutting Corbin’s authority. Corbin's relationship with the board continued to decline and in June 1902, the Trustees voted to replace him, appointing Tuskegee graduate and Booker T. Washington protégé, Isaac Fisher.

As in 1873, Corbin’s Arkansas story might have ended there: persistence and a sense of mission ultimately checked by politics. But Joseph Carter Corbin had put down roots in Arkansas, in Pine Bluff—and he would not be moved. Instead, Corbin remained in Pine Bluff, serving as principal of that city’s Merrill High School. And there he stayed, doing the work that he had found for himself—or which had found him—in Arkansas. His wife, Mary Jane Corbin, died in 1910; he followed on in January of 1911.

There is much more to Joseph Carter Corbin’s story than I had time to relate or comment on that day; Dr. Finney’s book is the best place to start. That afternoon, I think that everyone on the program found that they wanted to say more than there was time for, but never mind: the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff has the next two years in which to celebrate its 150th birthday, so there should be other occasions, certainly on Joseph Corbin Days yet to come, days on which to visit the Pine Bluff campus, “the house that Corbin built.” Si monumentum requiris, circumspice.