History

1833 - 1859: Capital For A New State

Governor John Pope

In the 1820s, westward migration increased the population of Arkansas until it approached the threshold required for a territory to apply to become a state. In 1829, President Andrew Jackson appointed John Pope, a prominent lawyer and former U.S. Senator from Kentucky, as the third territorial governor of Arkansas. When Pope arrived in Little Rock, he found a town of approximately 976 people. Trees covered the area, and trails rather than streets led from house to house. About 60 buildings were situated in what would now be considered the immediate downtown area, with the majority being log cabins. Government buildings were actually wooden shacks and were in terrible condition. For several years before Pope's arrival, the Territorial Legislature and Superior Court met primarily in rented rooms. Shortly after assuming the post of territorial governor, Pope submitted a request to the U.S. Congress for aid in financing a territorial capitol. Granting his request, Congress passed an act which gave Arkansas ten sections (6,400 acres) of land which could be sold to raise funds for site selection and construction. The Territorial Legislature was responsible for the sale, and received three proposals concerning the ten sections of land. The most popular was a proposal submitted by Robert Crittenden, a leader in Arkansas politics and an influential man among many members of the legislature. Crittenden offered to trade his two-story brick house (located on the block where the Albert Pike Hotel now stands) for the 6,400 acres of land. He assured the Legislature that this would provide immediate and suitable quarters for the territorial capitol. Crittenden's followers quickly passed a bill in support of the exchange. However, Pope vetoed it on the grounds that the ten sections were worth far more than Crittenden's home, and that Congress donated the land to enable the territory to secure a state house, not a dwelling house as a temporary arrangement. Time proved the wisdom of the governor's veto. Within two years, Pope sold the ten sections for $31,700, and in the same year, Crittenden sold his home for $6,700. By this time, Congress had given Pope authority over the matter.

Designer Gideon Shryock

Gideon Shryock of Lexington, Kentucky, who designed the state capitol for Kentucky, was asked to draw the plans for the building. He prepared the plans but was unable to come to Arkansas himself to supervise the work, and instead sent George Weigart in his place. The plans were splendid, but far too elaborate and expensive for the funds and land available. The plans were modified before work began, presumably by Pope and Weigart. Construction on the building began in 1833. There were to be three buildings—a main building with two buildings on each side and covered walkways to connect the buildings. The main building was to have two fronts—a river facade and a street facade. Advertisements were run in the Arkansas Gazette weekly requesting bricklayers, stonemasons and laborers (preferably slaves and boys from the country) to whom $10 to $12 would be paid. Much material for the building was obtained locally, even bricks which may have been made on-site with slave labor. The State House served as the state capitol until 1911, when construction was completed on a new building, located at what is now Capitol Avenue and Martin Luther King Drive. For more on the history of the building, see the Pillars of Power exhibit.

The Building Opens

By 1836, when the building opened its doors for the first general assembly, Arkansas had become a state. Six years later, in 1842, Governor Archibald Yell declared that the building was complete. When Arkansas became a state, government officials moved into the new building, despite ongoing construction. In fact, Arkansas legislators threatened workers with bodily harm because of construction noise during the session.

Legislative Disputes

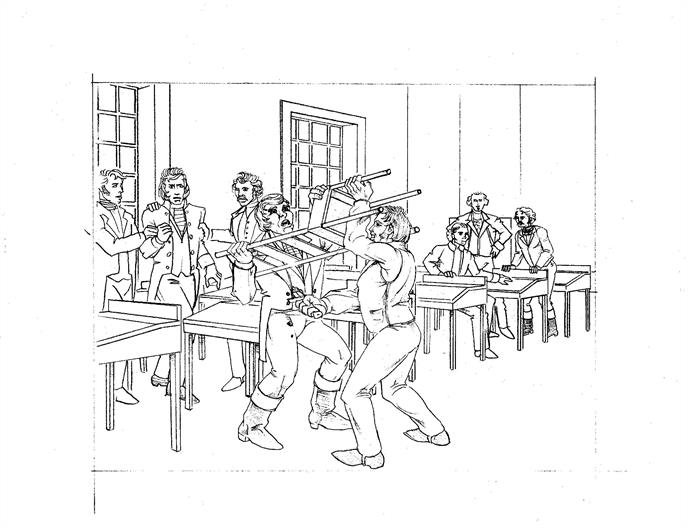

Land speculators grew rich during the settlement of frontier Illinois and Missouri in the 1820s. Similar-minded entrepreneurs expected to fare likewise in the new state of Arkansas. To facilitate this, the new state government created state banks. Unfortunately, these were chartered on the eve of the Panic of 1837, one of the worst depressions in the nation's history. Founded on the unrealized expectation of a rise in land values, these banks faced a crisis from the start. Dispensing blame for the failure of the state banks became the most contentious political issue of the day. This was the climate in 1837 when State Rep. Amos Kuykendall proposed a bill to award a bounty on wolf hides. The discussion stalemated on the issue of how the bounty would be dispensed. Were cash-strapped local magistrates to pay and then be reimbursed? Would they be required to hang onto the smelly pelts as proof? Someone suggested that the hunters be issued some sort of certificate.

At this point, Rep. J.J. Anthony of Randolph County rose and suggested the hides be signed by the president of the Real Estate Bank. The implication was that this would make them legal tender, a subtle criticism of the alleged value of the banknotes in circulation. The joke was so subtle, in fact, that no one understood it, least of all Speaker of the House John Wilson - who happened to be the president of the Real Estate Bank. Wilson asked Anthony if he intended an insult. Anthony refused to clarify his remark.Wilson declared Anthony out of order and ordered him to be seated. Anthony refused to yield the floor. According to one witness, he supposedly opened his coat at this point to reveal his knife. Other versions indicate it was Wilson who first brandished a weapon.

Events quickly escalated and the two antagonists rushed toward one another in the aisle. Rep. Grandison Royston thrust a chair between the two men, hoping to separate them. Anthony and Wilson each grabbed the chair and began to duel with their knives. Anthony slashed Wilson's wrist, but Wilson then rushed forward and plunged his knife to the hilt directly into Anthony's heart. Death was instantaneous.

Capitol In Need Of Repair

The capitol remained basically the same architecturally for the next 43 years. On the inside, however, the building needed constant repairs. Problems appeared as early as 1837, when the beams in the roof of the main building (what is now the House of Representatives) began to shrink and fall as much as eight inches. Two years later, the main walls in the west wing gave way in several places. The plaster in the ceiling of the senate chamber also began to fall. The grounds were in poor condition as livestock from a nearby stable often wandered through the yard. Also, windows were repeatedly broken by vandals, and the furniture was basically stark and bare, with sawdust covering the wooden floors. Yearly, the secretary of state asked the legislature to allocate money for patchwork repairs. While lawmakers were not blind or insensitive to the conditions, Arkansas was far from a rich state, and there was simply not enough money left over after attending to pressing financial matters.

Secession And Civil War 1860-1865

The Old State House served first as the Confederate and later the Union capitol during the Civil War. The building's furnishings were looted by each army when they departed the structure.

The first Confederate governor was the unpopular Henry Massie Rector, who fled Little Rock in May, 1862, when it appeared Little Rock would fall following the Battle of Pea Ridge. Unfortunately for Rector, the Union forces elected to retire to Helena on the Mississippi River.

"We would be glad if some patriotic gentlemen would relieve the anxiety of the public by informing it of the locality of the state government," a newspaper belonging to Rector's rivals mocked. "The last that was heard of it here, it was aboard the steamer Little Rock about two weeks ago, stemming the current of the Arkansas River."

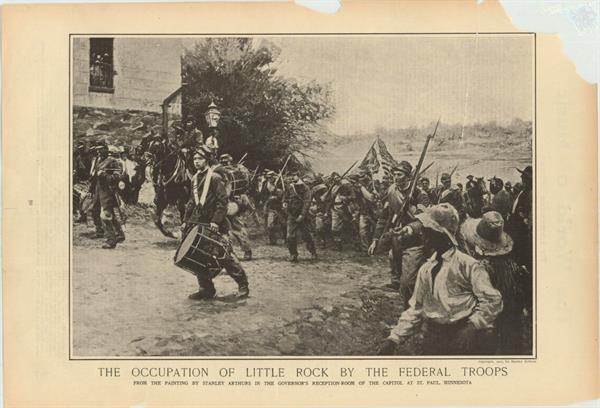

Rector's humiliation was complete when he was not re-elected that fall. Less than a year later, however, his successor, Harris Flanagin, was forced to flee as Little Rock fell to Union forces on September 10, 1863.

For a time, Gen. Frederick Steele quartered part of his army at the State House. B. F. Simmons, a soldier barracked there, wrote to his family: "…The 3rd Minnesota was detailed as Provost Guard for the city and quartered in the State House. We're having a time of it, we walk on fine carpets, sit on large cushioned chairs, sleep on spring beds, and aluminate (sic) over fine rooms…."

Early in 1864, Gen. Frederick Steele ordered repairs to the State House, though these were cut short by his march to Camden in the spring. The building was then turned over to a Union government headed by Isaac Murphy. In 1866, after the war ended, Robert J. T. White, Murphy's Secretary of State, reported on the status of the State House:

"The windows have been renewed and painted in a neat and substantial manner; and as a measure of police, as well as convenience and comfort to the public officers and approaching future legislatures, the gas fixtures have been replaced with some improvement in arrangement...

"I have made arrangements with Mr. F. J. Ditter, by which the two legislative halls will be supplied with suitable furniture, including carpets, chairs, desks, etc., all of the originals of which have disappeared during the war."

In 1863, during the midst of the Civil War, Little Rock fell to Union forces, and the Confederate state government moved the capitol to Washington, Arkansas, leaving the State House to be occupied by Union troops. The troops remained at the State House for seven months and then marched to Camden, leaving the capitol in the hands of a Unionist governor, Isaac Murphy. Murphy had the windows renewed and painted, gas light fixtures replaced and rearranged, and the floors and grounds cleaned up. After the Civil War, during the 1866-67 legislative session, the governor and secretary of state convinced legislators that the building was falling into decay, and certain ruin was inevitable unless something was done immediately. Money was allocated to rebuild the walls of the west wing and the main building, making it a one-story connection and thus providing desperately needed office space. At the same time, the stairway in the west wing leading to the executive offices was moved outside, providing an open-air stairway. To this day, why it was moved outside remains unclear.

Reconstruction And The Brooks-Baxter War 1865 - 1874

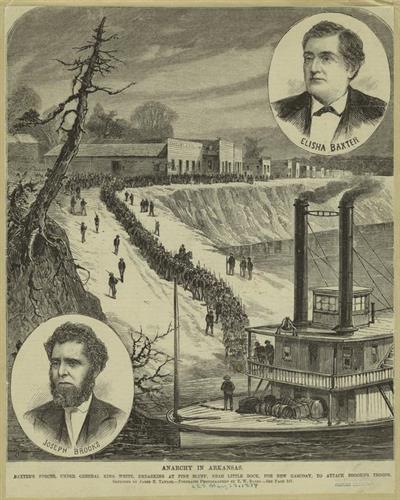

By the 1872 gubernatorial election the Arkansas Republican party had split into two factions. One group was known as the Minstrels and consisted of Powell Clayton supporters. The other group, called the Brindletails, was led by Joseph Brooks, an Iowan who came to Arkansas to work with the Freedmen after the war. In that election, the Brindletails nominated Brooks for governor and secured the support of the state's Democrats by promising universal amnesty and a restoration of voting rights to any former Confederates who remained disenfranchised. The Minstrels, who lost their most viable candidate when Governor Clayton was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1871, chose to nominate Elisha Baxter, who also promised amnesty.

During the state election, voter fraud and intimidation were widespread. Election results were challenged and the returns thrown out in four different counties. Officials took two months to certify the returns. Modern scholarship suggests that Brooks probably won the election, but the state election commission issued the certificate of election to Baxter. Baxter took office on January 6, 1873, despite the fact that Brooks signaled his intention to challenge the election results.

Brooks first appealed the election commission's decision to the General Assembly, but most of the members were Minstrels and the legislature never considered his case. Then, Brooks found a friend in John "Poker Jack" McClure, State Supreme Court Justice and editor of the Little Rock Daily Republican. Building support among moderate Democrats, Baxter transferred the state printing contract from McClure's Daily Republican to theArkansas Gazette. In the summer of 1873, in alliance with the state's attorney general, McClure instituted legal proceedings to have Baxter replaced by Brooks. Brooks's bid failed in the courts, and Baxter's tenure of office appeared solid.

In March, 1874, however, Brooks's opportunity was revived when the entire Republican leadership broke with the governor after he not only refused to issue bonds to the Arkansas Central Railroad, but also contended that the bonds issued by the state during the Clayton administration were unconstitutional. This was a major threat to the state's railroad interests, who had close ties to Republican leaders. As a result, the Republicans pushed forward Brooks's legal challenge to Baxter, which had languished on the Pulaski County Circuit Court docket. When Baxter's attorney did not appear before the court, the judge named Brooks as the legal governor.

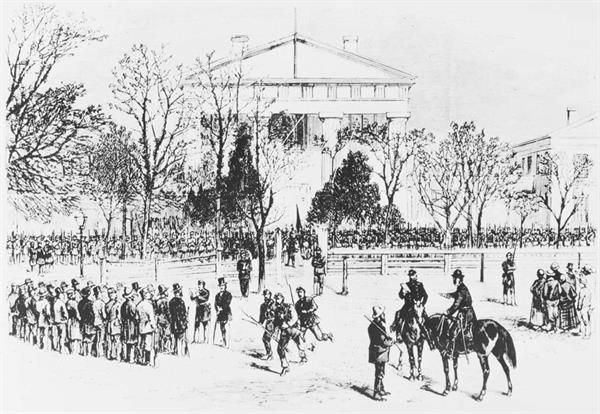

On April 15, having been sworn in by the chief justice of the state supreme court, Brooks, with the support of armed men, entered the State House and removed Baxter. Baxter simply moved down the street to the Anthony House and continued to act as governor. Supporters of both men came to Little Rock, where they were organized into armed bands. Their presence ultimately produced conflict. Baxter's militia dispersed a pro-Brooks force which organized in Jefferson County. Fighting also erupted on the streets of Little Rock. Modern historians have estimated that between 50 and 200 men died in these skirmishes.

The final decision about the governorship was not decided by arms, for Brooks and his supporters realized that ultimately they needed the support of the federal government to win. By 1874, however, President Ulysses S. Grant was unwilling to act to sustain Republican governments anywhere in the South and indicated that Brooks would receive no support. Instead, he urged both parties to put the election in the hands of the state legislature. While Brooks did not agree to this solution, his supporters disbanded and on May 15, Baxter returned to the State House. The legislature he called moved to settle the constitutional crisis by asking the voters to call a new constitutional convention.

The convention met on July 14 and produced a proposed constitution that was essentially a repudiation of Reconstruction. In September, the delegates to the Democratic State Convention twice nominated Baxter for governor, but he politely declined each time. The Democrats then nominated Augustus H. Garland. On October 13, 1874, in a general election in which the entire electorate was allowed to participate for the first time since the war, voters overwhelmingly favored the entire Democratic slate and the proposed new constitution by a margin of more than three-to-one.

For a more detailed examination of this incident, see "The Brooks-Baxter War," by Richard Owings, re-printed with permission from the Arkansas Times.

RENOVATION AND A NEW CAPITOL 1875-1911

Ten years later, repairs were performed to the Senate and House chambers, in addition to the executive offices. In an attempt to beautify the grounds, a bronze seal of the state of Arkansas was placed over the main entrance, and the Ladies' Benevolent Association of Little Rock and Pine Bluff contributed a large bronze fountain for the south lawn. In 1882, the grounds were enclosed down to the railroad tracks, sodded with grass, and trees planted as well. Despite the improvements, the governor, even after the remodeling, had to beg legislators to keep the building and grounds clean of rubbish for the sake of visiting strangers. Over the next ten years, visiting out-of-state journalists wrote of the state capitol's dilapidated, plain and shabby condition. A reporter from the New York Tribune wrote, "The halls and stairways are shockingly dirty, the walls are defaced with pencil inscriptions, the bricks of the lower floor are badly worn and dislocated, and the stucco on the columns of the Doric porticos is fast losing its grip."

Either through shame or necessity, the Legislature authorized money in 1885 for an almost complete renovation of the building. The building underwent dramatic changes in architectural style.

New furniture and carpeting were added to several rooms, and the brick floors in the main building's first floor were ripped out and replaced by poured concrete. A steam heating system was installed, replacing stoves and fireplaces, and an armory housing arms and ammunition was built on the grounds behind the capitol. Although over $30,000 was appropriated for the renovation, it was not enough. Within the next 10 years, dirt and moisture transferred into the building by foot traffic and open windows created havoc on the wooden floors, causing them to rot, and walls began to crack due to poor ventilation. The roof was in such poor condition that rain penetrated various rooms, causing discoloration and mildew. Even the new steam heating system needed overhauling four years after installation. Just five years after its renovation, the only complimentary thing said about the appearance of the building in the Guide to Little Rock, published in 1890, was "The prettiest thing about the State House is the lovely little park in front of it." Regardless of the continuing poor condition of the building, after the 1885 construction there was now enough space to house the three branches of government.

Additionally, the building housed the Superintendent of Schools office, two auditor's offices, the State Land Commissioner's office, the Bureau of Mines, Manufacture and Agriculture, and a display room for use by that bureau. While the rooms were not large, for a time they provided adequate space.

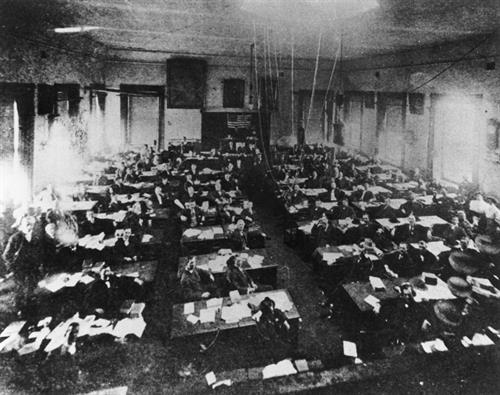

The medical school's use of the entire building from 1912-1935 was liberally supported by the General Assembly of 1913. Several structural changes were made in the building when the medical school moved in, although little or no redecorating or repairs were done once the state government moved out. Numerous partitions were erected to multiply the rooms since more space was required for the classrooms, laboratories, and offices of the medical school. The first floor of the central section of the building housed a general laboratory, a storeroom, a bookstore, a research lab, two lecture rooms, and the dean's office. On the second floor of the central section, the old Senate chamber served as a lecture hall, while the House chamber was divided by partitions into six rooms. These rooms were used as laboratories, a museum of pathology, an office area, a darkroom, and a storeroom. The first floor of the east wing of the Old State House was designated as the Department of Chemistry, and was divided into eight rooms used as laboratories, an office, a storeroom, and a lecture room. The Departments of Anatomy, Histology, and Embryology were located on the east wing's second floor, and included research laboratories, general laboratories, office space, and the dissecting room. Most of the cadavers used in the labs were either kept in the old Supreme Court library, which was divided into two rooms, or in the basement of the building. Little is known about the Arkansas Medical School's occupancy in the west wing of the building, except for the library and a laboratory on the first floor. In 1921, while the medical school was still settled in the building, the former state house was named the Arkansas War Memorial Building, and was "dedicated to the use of the American Legion, American Veterans of World War I, United Spanish War Veterans, Veterans of Foreign Wars, and all other statewide, non-profit organizations."