Thomas Chipman McRae came to the governor’s chair late in his life amid the social and economic convulsions that dominated the beginning of the post-World War I era. As one who had known economic hardship, he dedicated his governorship to education, economic progress and governmental modernization while resisting some of the social movements that erupted at the close of World War I.

McRae’s family had moved to Arkansas from North Carolina in the early 1840s and established a farm in the Mount Holly Community in Union County. The McRaes became prominent community leaders and were faithful members of the local Presbyterian Church. The Civil War brought economic hardship to the family, especially after McRae’s father died in July 1863. McRae was only 11 years old, but as the eldest son, he was responsible for running the family farm and providing for his mother and five siblings from that point forward. He also worked for a time as a courier for Confederate troops stationed in the rump state capitol at Washington.Thoughts of education waited until after the war and his mother’s remarriage. After attending a series of schools, he worked as a store clerk in Shreveport, Louisiana, attended Soule Business College in New Orleans and graduated from Washington and Lee University in Virginia with a law degree in 1871. At the age of 22, he set up a law practice in Rosston. His practice became more lucrative, and his influence grew.

He married Amelia Ann White, the daughter of the Nevada County Clerk, and the marriage produced nine children, of whom only five lived to adulthood. When the county seat was relocated to Prescott in 1877, the McRaes moved there and constructed a home known as “The Oaks,” which became the hub of family activities for more than 50 years.

Not long after moving to Prescott, McRae was elected to the state House of Representatives, where the young solon won attention as a resolute opponent of the repudiation movement, which sought to cancel the part of the state’s bonded debt known as the “Holford Bonds.” The Holford Bonds were a series of real estate bonds connected to the early statehood railroad era Real Estate Bank that were defaulted on by the state and sold by a New York bank to James Holford, a banker in London, England. McRae stated that the bonds were legitimate debt that the state should honor, which was an unpopular stance after the Civil War.

He then held a series of local positions, leading to his election to Congress from the Third District in 1884. For 18 years, he was considered to be one of the most effective members of the House of Representatives, particularly noted for legislation that returned unearned railroad land grants to the public,established the basis for the National Forest System and reserved land grants for sale to actual settlers rather than land speculators. By the time he retired in 1903, his was the longest period of service of any congressman in Arkansas’s history.

Upon his return to Prescott, he concentrated on his law practice and his purchase of the Bank of Prescott in 1905. As president of the Arkansas Bankers Association in 1913, McRae drafted model legislation that regulated state banks, and he actively advocated for the Federal Reserve Act. He continued to be active in Democratic Party politics and was elected president of the Arkansas Bar Association in 1917.

He served as a delegate at the 1917 Constitutional Convention, where he advocated for progressive reform, like including woman’s suffrage. However, voters rejected the proposed constitution in 1918.

This rejection, along with convulsions that wracked Arkansas such as the rise of the Second Ku Klux Klan, the Elaine Massacre, anti-Prohibition sentiment, railroad strikes and a sharp economic slump in 1919 and 1920, made strong, principled and respected executive leadership more important than ever. McRae had resisted calls to run for governor in 1913, but in 1920 at age 69, he reluctantly stepped into the fray.

After a strenuous race in which McRae was accused by rivals of being the candidate of “vested interests” (i.e. bankers) who would force the state to pay the long-since repudiated Holford Bonds,McRae was elected governor in 1920 on a program of improved education, fair taxation, an equitable road program and the abolition of unneeded government positions.

After a solid win in a crowded Democratic Primary, McRae won nearly 65 percent of the November vote against Republican lawyer Wallace Townsend and Josiah M. Blount, an east Arkansas school administrator who ran as a Black and Tan Republican. The splinter group consisted of African Americans in the Reconstruction-era South who were loyal to the Republican Party. They stood against the “Lily Whites,” which was a group of Republicans who promoted the removal of black people from offices in order to maintain political power.

McRae’s progressive program in 1921 quickly slammed into the realities of serving alongside a state General Assembly that was as reactionary as any since the end of Reconstruction. Its chief failure was in the highway situation, a scandal which caused heavy embarrassment to Arkansas and to McRae’s new administration. The issue was a network of hundreds of local improvement districts that were empowered to issue bonds for road construction with little or no state supervision and with the payments of the bonds landing solely on the backs of property owners. The lack of accountability also led to widespread fraud.

Realizing that matching funds from the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads were in jeopardy, McRae invited officials from the federal agency to assess the situation. Their report became the basis for the plan he presented to the General Assembly in February 1921, but it was quickly quashed in the Senate. One part of his plan that survived was Arkansas’s first gasoline tax, which was a one-cent-per-gallon levy that, when combined with increased registration and licensing fees, began to shift the burden from property owners to road users.

Yet outrage over the mismanagement of the road districts, which Sens.Joe T. Robinson and Thaddeus Caraway called the “rottenness in Arkansas,” brought the state unwelcomed attention from Harding’s administration and the U.S. Congress. In November 1921, Congress mandated withholding federal funds from states where highway departments did not have control of road projects.

Despite this mandate, the 1923 Arkansas General Assembly refused to centralize highway authority again. As a result, the federal government withdrew highway funds and technical support.

Despite this mandate, the 1923 Arkansas General Assembly refused to centralize highway authority again. As a result, the federal government withdrew highway funds and technical support.

The governor called lawmakers back in September 1923, and they passed the Harrelson Road Law. The act gave the state sole supervision over construction and maintenance of highways,increased the fuel tax to 4 cents per gallon to retire the debts of the improvement districts and financed the work of the reorganized department. This proved to be the longest lasting accomplishment of the McRae administration.

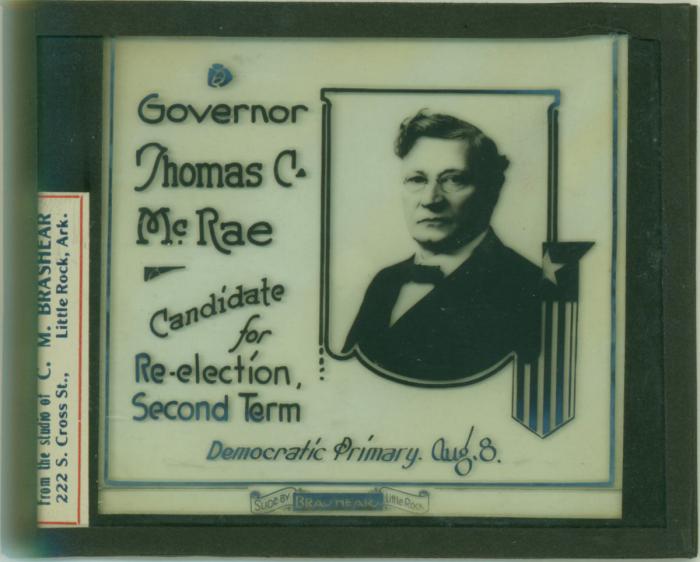

McRae readjusted the state property millage to stabilize funding for the University of Arkansas but accomplished little else from his first legislature. Winning a second term in 1922 by large margins in the primary and general elections, he interpreted it as a mandate for further reforms. However, he encountered as much resistance in his second term as in his first.

With great difficulty, a severance tax was passed in 1923 with the revenues earmarked to fund public schools. Lawmakers also approved his proposals to create a state geologist’s office and to authorize the Railroad Commission to regulate procedures used in oil production, a reaction to the development of the new fields in southern Arkansas.

McRae recommended a tax on net incomes, not profits, but the legislators preferred a tax on cigars and cigarettes that raised much the same amount as the income tax. After the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional, the legislature came back and rewrote it to pass court muster. By the time McRae left office in January 1925, public school finances had a stability they had not known before.

Topping these accomplishments off with improved support for the National Guard, a first-ever tuberculosis sanitarium for African Americans and a large state budget surplus, the 74-year-old McRae returned to Prescott to his banking interests and law practice. The last major state leader of the Progressive Era and Arkansas’s oldest chief executive survived his term by four years and left a legacy of political moderation and commitment that brought Arkansas’s government and economy into the modern age.