Just for the love of the work...

Makers Arley Payne, Arthur Arlington Castera, and “the elusive Ex-Confederate' certainly fit Ethel C. Simpson’s summarization of early settlers of the state as being individualistic, self-sufficient, and carrying an air of general orneriness. Though none of these men were trained as professional artists or artisans, they nevertheless expressed their individual creative spirits through the pastimes of drawing and carving. Sketching and horn carving were typically reserved for old men and the infirm – people who could not otherwise perform the hard labor required of most turn of the century Arkansans. Able to create anywhere and with simple tools, these makers took their romantic notions of life, love, and sport, and transformed their daydreams into whimsical creations.

Six Wheeled Machine of Time, Arley Payne, Paragould (Greene County), July 14, 1909, pen-and-ink on paper, 9 ¼ × 11¾ in., collection of Historic Arkansas Museum, Gala Fund Purchase honoring Carrie and Tyndall Dickinson, 99.42.102

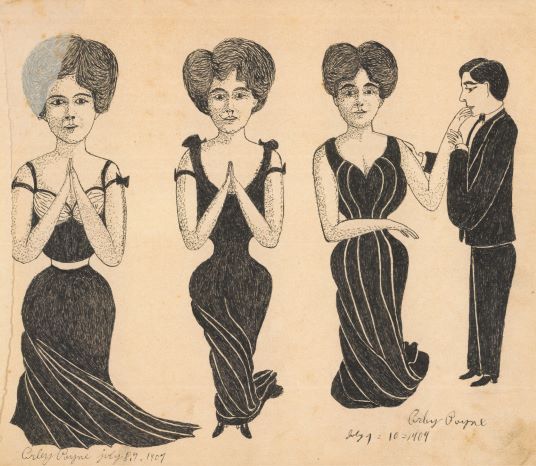

Untitled (Three Ladies and a Gentleman), Arley Payne, Paragould (Greene County), 1909, pen-and-ink on paper, 9 ½ × 11 ¾ in., collection of Historic Arkansas Museum, Gala Fund Purchase honoring Carrie and Tyndall Dickinson, 99.42.102

When four sketchbooks, filled mostly with cartoonish copies of images from ladies’ magazines dating to the turn of the century, were donated to Historic Arkansas Museum in 1999, HAM researchers were perplexed. The sketchbooks came with a name – Arley Payne – and staff initially assumed the person who created these unusual drawings was a woman. However, after closer examination of the sketches and hours of sleuthing, the true artist was discovered – Arley (also Arlie) Cornelius Payne, a young man born in Paragould (Greene County) in 1888. Very little it known about Payne, so it is unclear whether his artistic pursuits continued beyond his youth. Though he enlisted and served in World War I and worked for a brief stint as a photographer, he lived with his mother in Paragould for most of his life. None of the available records show that Arley Payne ever married or indicate that he ever held a long-term job.

These pen-and-ink drawings, created when the artist was twenty-one, are two of many cartoons contained within four sketchbooks that Payne filled between the years 1908 and 1911. In his marvelous series of cartoons, the artist pairs the exploration of popular themes such as romance with more whimsical material including this “six wheeled machine of time [travel].” Many of his drawings are copied from popular early twentieth century advertising campaigns and fashion illustrations, while other images are clearly born from his robust imagination. Payne seems to have been an ornery (or at least mischievous) creature, who expressed himself in his early 20s through these originative sketchbooks.

William Kavanaugh Hunting Horn, maker known as the “Ex-Confederate Soldier,” Little Rock (Pulaski County), December 25, 1899, cow horn, relief carved, 11 in., collection of Historic Arkansas Museum, gift of Ms. Emily Hall, 2003.100.2

C. V. Dixon Hunting Horn, maker unknown but possibly the “Ex-Confederate Soldier,” maker of the Kavanaugh horn, Walnut Lake (Desha County), 1892, cow horn, relief carved, 11 ¾ in., collection of Historic Arkansas Museum, Gala Fund Purchase Honoring French Hill, 2004.27

H. J. Williams Plum Bayou Hunting Horn, maker unknown but possibly Arthur Arlington Castera, Plum Bayou (Pulaski County), April 1914, cow horn, relief carved, 11 in., collection of Historic Arkansas Museum, Gala Fund Purchase Honoring Carrie and Tyndall Dickinson, 2000.13

A distinctive group of five hunting horns, believed to have originated from the Wampoo and Eagle townships (Pulaski County), are so similar in their design that they appear to have been carved in the same “school,” or style unique to a small number of makers.

Thus far, only two makers of this style of horn have been discovered, and both men lived in vicinity of the Wampoo Township, roughly twenty-five miles southeast of Little Rock and thirty miles from Pine Bluff. One artisans remains unnamed but was referred to as “the ex-Confederate” and creator of a horn inscribed “W.M. Kavanaugh.” According to an 1899 article in the Daily Arkansas Gazette, “Sheriff W. M. Kavanaugh yesterday received a pretty souvenir in the form of a hunting horn. It was carved out by an ex-Confederate soldier living near Wampoo in Eagle Township, his tools being a pocket knife, an awl and a piece of sandpaper. The carving is very handsome and the following inscription is carved in raised letters: ‘W. M. Kavanaugh, Little Rock, Ark. Compliments of Dr. G.K. Mason, December 25, 1899.’ ”(Daily Arkansas Gazette, December 21, 1899, p. 5.)

A second newspaper article from 1910 described at length a hunting horn remarkably similar in design to the Kavanaugh horn. Journalists praised its creator, Arthur Arlington Castera. Details of his “excellent specimen of horn carving” and Castera’s life gives insight into how and why a rural early twentieth century Arkansan carved such an elaborate hunting horn:

'[A.A. Castera] says that he is a farmer and picked up the art while a boy. He has made most of the tools used in his work, being unable to buy them in the sizes required so that the strength would be great enough to cut this hard material of which the horns are formed. The work recently completed is the second of its kind made by Mr. Castera in the last five years. It represents more than a week of solid labor. It bears the name of the man for whom it was made and that of the maker in a corded scroll above which are the figures of a deer followed by a hound, all in raised work and not a single flaw can be found in any of the work.

'The mouthpiece was made from a separate piece of horn, carved in the shape of an acorn. The bell of the horn is bound by a hunting belt with a large buckle, making the whole make-up of the piece in keeping by representing the full scope of the sport of the hunt, the woods, the dogs, the deer and the heavy belts and trappings favored by the hunters. The work was not done for the appearance of the call alone, for the tone is perfect, showing that the maker has not overlooked a single item it its making. Mr. Castera says that he has never considered his work good enough to warrant his giving up farming, and that he does the carving in his spare moments, just for the love of the work. He has a perfect conception of the deer at speed until none of the lines in his work are exaggerated. The horn carving has always been considered rather lightly as a suitable pastime for old men and those unable to do hard work, but the specimen...proves that there is as much art in that kind of work as there is in painting or another kind of carving, and for those who are particular and up to the minute in their hunting paraphernalia, a horn of this kind would be necessary to complete their outfits, one that is not to be thrown in an out of the way place while not in use, but one that could be shown with pride by the owner and as an ornament in rooms of the foremost elite furnishing.' (Daily Arkansas Gazette, December 5, 1910, p. 10.)

The horns made by Castera and the “ex-Confederate” share so many qualities that it is probable the two men knew each other and shared techniques and design ideas. They may be the creators of most or all of these distinctive “Wampoo” horns.