By Kathryn Bryles

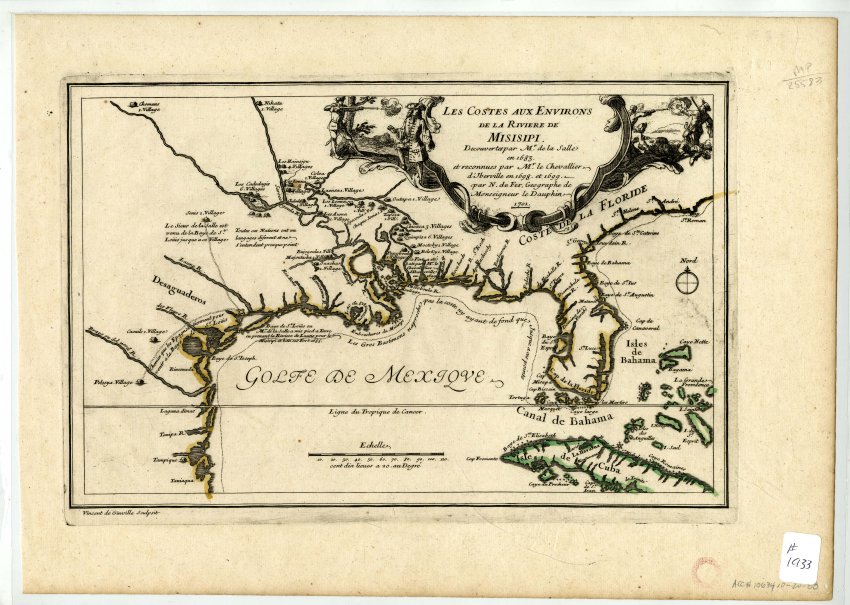

Prior to La Salle’s voyage down the Mississippi River and into Texas, the interior of North America was a vast blank space on European-made maps. Cartographers used this to their advantage as a way to put their artistic skills on display. Indigenous tribes and wild animals encountered by early explorers were drawn in the open spaces, advertising the danger and excitement awaiting European settlers of the New World. Until the 19th century, North American maps focused on the Eastern and Southern coasts due to the placement of port cites, the life lines of trade for European colonizers. But with La Salle’s venture into the heart of North America, these vacant spaces began to display more accurate landmarks.

The son of a wealthy merchant from Rouen, France, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle began his career as a Jesuit priest. At the age of fifteen, La Salle gave up his large inheritance to enter the clergy. Seven years later, bored with life at the monastery, he requested to join his brother, a priest of the Seminary of St. Sulpice, in New France (now Montreal). However, upon his arrival in the New World, La Salle asked to be released from the priesthood entirely, due to “moral weakness.” Luckily, or perhaps as part of an intentional grand strategy, he received a land grant from the Seminary of St. Sulpice, which provided grants to European settlers around the Island of Montreal to create a protective buffer between the seminary and nearby Iroquois. Friendly trade relationships with members of the Mohawk tribe eventually led to La Salle’s interest in opportunities related to exploration of the Ohio River.

Consumed with finding a North American river trade route to China, La Salle attempted to gain permission from King Louis XIV to explore the area south of New France. After two separate trips to France, Louis finally granted La Salle permission to begin his expedition. He returned to Montreal in 1678 to construct a fort along the Niagara River. There, he built the first commercial vessel on Lake Eerie, The Griffon, which he planned to sail down the Mississippi River. However, before he could set sail in 1679, The Griffon was destroyed by a storm, a mutiny, or some combination of the two.

La Salle’s expedition finally left New France in 1682, reaching the Gulf of Mexico in April of that year after two months of difficult travel. La Salle laid claim to the region, naming it “La Louisiane” after King Louis XIV. With the assistance of Henri de Tonti, La Salle forged alliances with Native American tribes he encountered along the way. They explored the region near the mouth of the Arkansas River, and de Tonti received a grant of land nearby. De Tonti remained at Fort Saint Louis, a fur trading post along the Illinois River, while La Salle returned to France to collect settlers to populate this newly established region.

In 1684, two years after La Salle’s first adventure down the Mississippi, he once again set sail for North America, this time to establish a French colony in Louisiana. He departed France with four ships and 300 sailors, all headed toward the mouth of the Mississippi River. La Salle’s woes began even before they reached the shore, when pirates sunk one of his ships in the West Indies. Then, La Salle argued with the expedition’s navigator, resulting in a landing at Matagorda Bay (near modern-day Houston, Texas), 500 miles off course from their destination. Upon their arrival at Matagorda Bay, the errors of a drunken pilot sunk the second of his four ships. With the crew of that ship now stranded, La Salle decided to lead an expedition inland, following a nearby river.

However, his land expedition was similarly beset by trouble. Both his compass and his astrolabe were broken, so he relied on the sun and outdated maps to orient himself. La Salle believed his party had landed in Espiritu Santo, and that the river he encountered was the Escondido, since none of his maps recorded a similar river. Foolishly, he thought that following the Escondido would eventually lead to the Mississippi, proclaiming “the course of the Mississippi River during the last 100 leagues is exactly that of the Esondido.”

In Mexico, La Salle encountered sickness, supply shortages, lack of drinking water, as well as the death of many of his men, and one of his two remaining ships deserted and sailed back to France. By 1687, his original expedition of 300 had dwindled to just thirty-six men. On March 19, La Salle’s remaining crew turned to mutiny, and the disgruntled sailors murdered La Salle, shooting him and three of his companions at point blank range.

La Salle’s navigational errors on his return trip to the mouth of the Mississippi River were due (at least in part) to the inaccuracy of early European maps of North America. For most of his initial journey down the Mississippi in 1682, he relied on the current of the river and the advice of the Native American tribes he encountered, through the translation efforts of Henri de Tonti. During the late 17th century, Henri de Tonti’s ongoing activities in La Louisiane encouraged the establishment of a permanent settlement in what would eventually become the state of Arkansas; Arkansas Post first served as a rest stop and trading post for people traveling between Illinois and the Gulf of Mexico. After La Salle’s failed second expedition in 1684-1687, trappers and traders began to move into the new region, and France eventually established the port of New Orleans in 1718. The arrival of traders in New Orleans led to increased surveys of the region and more accurate maps.

Visit "Acansa to Arkansas: Maps of the Land" in Historic Arkansas Museum’s 2nd Floor Gallery through January 5th, 2020, and see for yourself how La Salle’s expeditions shaped maps of North America made in the 18th century.