From the Director

April 2021

A few days ago, a patron called in with what seemed like a simple question. She really asked two related questions: what is it that historians and archivists do, and, beyond that, what do we mean when we say “history”? We talked back and forth for the better part of my lunch break, and with a scheduled video conference looming, I promised that I would give this some thought and put some ideas down on paper about this for her.

Since then, I’ve tried to come up with responses that don’t sound as though I am claiming that historians and archivists do everything but scrub the kitchen sink (and I promise you, we do this too…just not for professional credit). The problem is that the work of modern historians and archivists is a complicated business; it’s not just about doing quiet research in quiet research room settings anymore, consulting limited numbers of documents…that is, if it ever really was. This is as it should be, because history itself is a complicated thing—or, rather, a complicated bunch of things.

What do I mean when I say “history”? When I was a kid, growing up in a city full of big museums and surrounded by places where great things had happened, history was for me the past and the stories that survived from it, often associated with those sites, or the neat old stuff gathering dust in the various museums. History was what my favorite aunt, Mary Catherine Matosian, told me as we visited those museums, and it was what I learned from the hard-bound, well-read volumes of American Heritage that she kept in the full bookshelf in her living room. History, it seemed, stopped ten or twenty years before the present day, so the historical past was always growing, if not gaining on us. This didn’t mean, though, that history’s effects did not extend forward: “Aunt Mary C” showed me how the past lived into the present on street corners, in neighborhoods with old houses, in the names of streets and parks, in art and music and books good and bad and in the laws of the land. My aunt showed me that history was complicated—but cool.

Skip ahead a decade or six, and you find me with the same feeling toward what was a hobby then but has, somehow, become a vocation. How complicated is history? A short and incomplete list of what history is or may be considered to be should give you an idea:

History is the past—it begins a moment or two ago, and goes back to the first humans (or before, if one chooses to be a paleohistorian);

History is all that has happened in the past—all events, movements, deeds good and foul, great and minor, accompanied by bloodshed and charity, construction and destruction, bloviation and exalted oratory;

History is the record of the past—documentation left behind, in textual, graphical, aural or concrete forms, collected or otherwise preserved;

History is the profession of those who seek to preserve this documentation of past times (archivists, curators and librarians), as well as “historians,” who seek to make sense of it to ascertain both the “who, what, when, where and why (plus “how”)” of what happened, and its significance (what did causes and events mean to those who were involved in them, and what meaning can we take from them today?).

History is the work produced by historians of all sorts, both documentary and interpretive, which ensures that present and future generations will have the knowledge and tools with which to make sense of their own ever-growing past.

History, at least in the first two senses listed above, is not changeable—but our understanding of it is. The interpretation of the past should never be considered static: it can and must change according to new evidentiary discoveries, re-analysis of “known” documentation and even in consideration of consequences, intended and otherwise.

History is based on the best available facts and evidence: these constitute the “accurate” baseline of the discipline. Accuracy is, however, only one part of history: if it were the whole thing, then works of history would simply be works of exhaustive, faithful description, biography, and chronology. A good historian makes sure of his or her facts, then proceeds to argue from them. A poor historian (not a “bad” one, since this imputes evil intent or nature) does not—but can often be persuaded to improve their work by wider reading in and closer attention to that pesky evidence.

History is never complete. There is always room for new evidence, argument over its authenticity, debates over details, interpretation and significance---and this is what historians do, in person and in print, making sense of the past in new lights and new language for new audiences. We end up wrestling with the complications in order to sort out our pasts—and in so doing, the lucky ones among us—those of us with a sense of humor, maybe, or at least of irony--discover the cool.

--------------------------------------------------

There is something else that history is--or should be: fun. In support of this I point to the legions of historical reenactors and living history interpreters who make sense of the lifeways of the past by experiencing them and passing on to others what they learn. Some lucky few do this for a living, but for most, it is a recreation—I hesitate to call it a hobby—that allows purpose and pleasure, keeping alive the skills and details of daily life of decades or even centuries past.

A few weeks ago, I had the honor and pleasure of accepting an invitation to visit the Southwestern Regional Rendezvous, an annual event which brings together hundreds of men and women (and children and dogs) who enjoy re-creating the festive gatherings of the nation’s fur trade era, which stretched from the early Republic until, roughly, 1840. This year, the Rendezvous was sponsored by the Early Arkansaw Reenactors Association and hosted by the Nevada County Depot Museum of Prescott (well worth a visit, by the way) on the Prairie D’Ane battlefield near Prescott, site of a fierce fight during the Camden Campaign of 1864. I was assured that I might come as I was, but for the occasion I dug into my stocks of long-packed living history gear (a confession: during my misspent youth, a few hundred miles west of here, I peddled medicated soap, stomach remedies and an improved version of Perkins’ Metallic Tractors[1] to fur-trade reenactors) in order to blend in a bit.

The day was overcast and windy, the road in was bumpy and soft and the grounds were muddy, with a lovely gray muck that would color a battleship proud, but the welcome was warm, the coffee hot, lunch was tasty and it was clear that the participants were, in spite of battling the elements, enjoying their sojourn in past ways. I was particularly impressed by the research done by participants—craftspersons, traders and campers alike—into aspects of early American life and material culture. Woodwork, weaving and tailoring, beadwork and even tinkering were in evidence, and the practitioners “knew their onions.” The participants were tenting under proper canvas and many, if not all, had pitched their camps so as to minimize the chances for getting flooded out were rain to fall (which it certainly did!). Classes were offered, including one valiant attempt to teach the assembled crowd how to both properly cut a quill pen and to make ink from oak galls, as was the common practice in early America.

A living history purist might sniff a little at a few of the compromises that were visible, if one looked hard enough: Modern coolers or water jugs lurked under blankets or canvas, cots and air mattresses were covered by point blankets and the odd buffalo robe, and for many, rubber boots or even dutch-style klompen (wooden shoes) proved to be a better way to deal with the muck and mire than buckskin moccasins. For my money, though, these are style points that do not detract from the substance. The folks who made me welcome on the Prairie d’Ane were and are—next year’s event is already scheduled for Nocona, Texas—historians in a broad and good sense. They do their research, know what is and what is not historically appropriate for their chosen time period, preserve historic skills, are open to learning more and enjoy passing along that knowledge to others. They were good companions on a grey Nevada County afternoon and I hope to cross paths with them again.

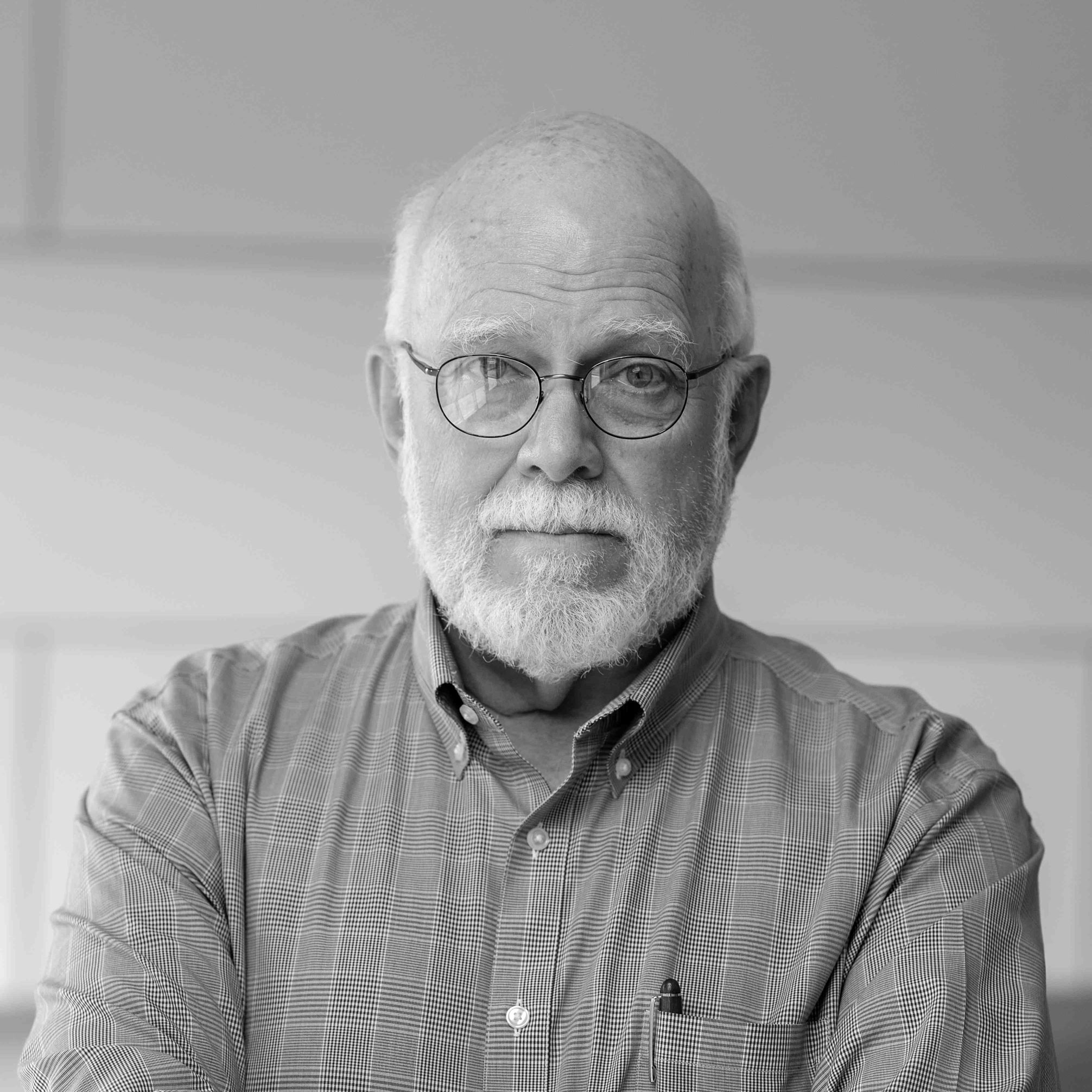

Dr. David Ware

State Historian

Director, Arkansas State Archives

[1] George Washington owned a pair; they at least satisfied the Hippocratic Oath’s proviso of “first, do no harm,” which could not be said for many other medical treatments and nostrums of the day, including the ones that hastened Washington’s death in 1799.